The collection tells a story...

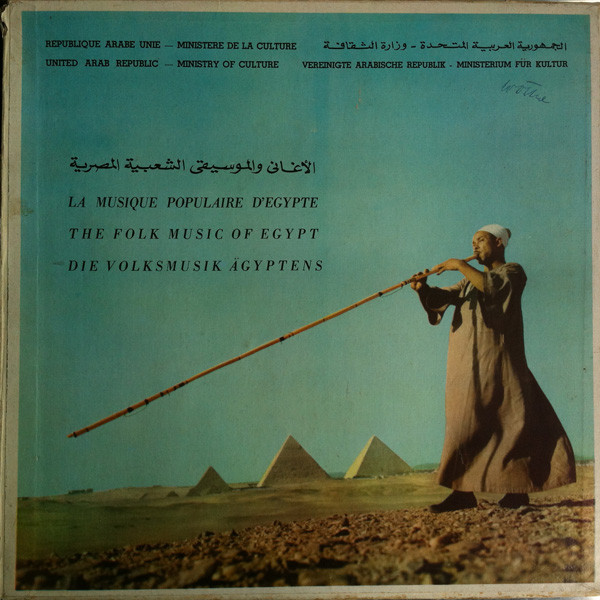

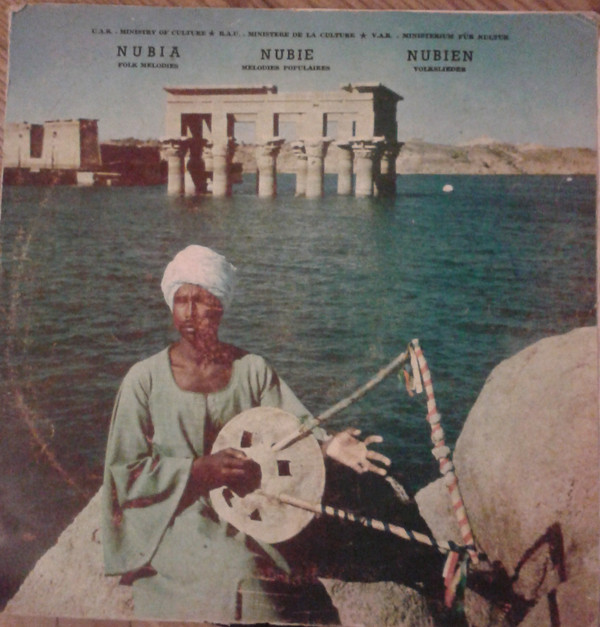

The published albums: The Folk music of Egypt (left); Folk melodies from Nubia (right). 1967.

The story of the Wahba-Alexandru virtual museum of Egyptian folk music at the Canadian Centre for Ethnomusicology (CCE)

In January 2017, the CCE unexpectedly and quite miraculously received a remarkable offer: a priceless treasure from Egypt. Not a mummy or a jewel encrusted pharaoh’s crown. Rather, an ethnomusicological trove of the sort one might hope to receive once in a lifetime: the complete set of fieldwork materials from a systematic Egyptian folk music expedition conducted in 1967 under the leadership of the celebrated Romanian ethnomusicologist and folklorist Tiberiu Alexandru (1914-1997), exactly 50 years after it had been collected.

This survey of folk music from around Egypt captured — in recordings, photographs, and field notes - a vibrant slice of Egyptian musical life that likely had evolved only slowly for many centuries, continuous even over several millennia, their roots stretching back to ancient Egypt. Sadly, over but half a century these traditions have since then almost completely disappeared. After 50 years most of the musicians are gone--this much is to be expected--but so are many of the instruments they played, the songs they sang, and even the musical genres themselves, first attenuated and finally replaced by popular, commercial, mediated music emanating from Cairo or Beirut. And whereas the mummies treasures of pharaoh’s tombs continue to be unearthed after thousands of years, the record of Egypt’s rich folk music heritage is much thinner. Music, unlike material culture, could not be preserved until the advent of recording technology early in the 20th century. Even then very little collecting was carried out in Egypt until Nasser’s nationalism stirred the creation of a folk music academy in the 1960s. Recordings were thereafter made, but not well preserved. The Academy’s rich archives, dating to the early 60s, languish, crumbling in Cairo’s heat and dust. As a result, the Tiberiu Alexandru collection is at present the oldest known systematic view of Egypt’s folk music available. The story of its preservation is miraculous in itself.

As Alexandru was not fluent in Arabic, he enlisted a research partner, then a young Egyptian Ministry of Culture employee named Emile Azer Wahba, who was instrumental in carrying out the project. Together they traveled throughout Egypt, making reel-reel recordings, taking photographs, conducting interviews with musicians, and transcribing lyrics, thoroughly documenting the musical traditions they encountered by traveling from village to village, from southernmost Egypt (Aswan) along the Nile River to the shores of the Mediterranean at Damietta; from the western desert oases to al-Sallum near the Libyan border, and east to Port Said and Suez.

.jpg)

The locations of folk music collection: from Aswan ("Assouan") in the south, to Siwa ("Sioua") in the west, and Port Said in the northeast.

This 1967 scan of Egypt’s contemporary musical wealth took place immediately prior to the devastating war with Israel which decimated Arab nationalism, and indirectly transformed the country from socialism to capitalism. Meanwhile advancements in electrification, and remittances coming from workers in the increasingly wealthy Arab Gulf, rapidly transformed Egyptian life - especially in the villages - bringing radio and television and providing the needed infrastructure for the rapid rise of popular music throughout the country, turning Egyptians from performers and appreciators of live folk music into passive consumers of musical commodities. Together with the rise of Islamism intolerant of music-making, the way was thus paved for unprecedented socio-cultural change, and tremendous musical losses. Indeed the culture gap between the 1960s and 1990s is, in many respects, probably far greater than that separating the 1960s from many centuries prior. With this historical backdrop, it is apparent that the Wahba-Alexandru collection is an invaluable musical portrait, representing a long period of Egyptian culture immediately before it was silenced.

The massive collection of tapes, photos, and notes was thereafter curated, resulting in two albums comprising about two hours of music:

- The Folk music of Egypt (al-Aghānī wa-al-mūsīqʾa al-shaʻbīyah al-Miṣrīyah). 1967. One 10" LP, 33 1/3 rpm

- Nubia: Folk melodies (al-Nūbah: al-alḥān al-shaʻbī ). 1967. Two 12" LPs, 33 1/3 rpm

First published by Egypt's Ministry of Culture, and distributed via Egyptian embassies throughout the world, the two albums were later released on cassette by the national recording company SonoCairo (Sawt al-Qahira). While relatively few copies exist outside Egypt, these folk music collections, due to their age and the great care with which they were compiled and produced, are absolute classics for ethnomusicologists studying the region. I remember very well perusing the beautiful photos of unfamiliar instruments - arghul, magruna - when studying Arabic music with AJ Racy in 1990, and many of my colleagues do as well. We listened to the music and read the notes with wonder - imagining an Egypt resonating with music of the earth, produced by clay drums, reed pipes and flutes, and coconut-shell fiddles, all manufactured locally, as well as regional instruments such as oud (plucked lute) and the imported violin. And the singing: rich voices emanting from men, women, and children, enunciating timbres through unfamiliar phonetics I could not yet understand.

However what we didn’t know at the time was that these two albums, totaling less than three hours of music in total, represent only a small fraction - around 12% - of the 25 hours or so Wahba and Alexandru actually recorded. Likewise, the LPs’ well-written liner notes distill but a small fraction of the dozens of interviews and photos gathered in the field.

In January of 2017, exactly 50 years since these now precious materials were recorded, I received a note from an ethnomusicological friend and colleague, the renowned qanunist and scholar Dr. George Sawa in Toronto, saying that a friend of his wanted to donate a collection of Egyptian folk music to the Canadian Centre for Ethnomusicology. This friend was none other than Emile Wahba himself. Now in his 80s, he had been living in Montreal for over 40 years, ever since emigrating to Canada in the 1970s. And throughout all those decades the precious 1967 fieldwork had been safely stored in an old Egyptian suitcase, in his home.

Thanks to funding from the Canadian Centre for Ethnomusicology, and the Department of Music through a President's Fund grant, this material was shipped to the University of Alberta, digitized, and annotated. We are in the process of preparing this database enabling both researchers, students and members of the interesting community to browse freely, by providing metadata for each object (notes, photos, recordings) as well as links indicating the relationships among items. We are grateful to CCE and Music, as well as the Arts Resource Centre for programming and digitization, and to the University of Alberta Library for providing backend storage on their ERA system.

Emile clearly conveyed to me that this fieldwork material was to be made public for research, scholarship, teaching, and general use and enjoyment, including creation of derivatives incorporated in additional media products. However the material may not be repurposed for commercial use without express permission from the Director of the Canadian Centre for Ethnomusicology, attributions must be retained in any usage, and new creations must be licensed under the same terms. These conditions are summarized in the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike (CC BY-NC-SA).